Maggie Hanna and the Central Grasslands Roadmap

Fourth-generation Colorado rancher Maggie Hanna has already lived several professional lives: ranch operator, rural mental-health advocate, philanthropic strategist, land-conservation leader and now director of one of the most ambitious grassland conservation efforts on the continent. But for Hanna, who grew up on her family’s woman-owned and operated cow-calf ranch in Fountain, Colorado, just 12 miles from the fast-expanding Colorado Springs metro area, the trajectory makes perfect sense.

Photo @Maggie Hanna

Ranching and working on the land is in her family’s DNA. Raised with a deep reverence for the land, she learned early that a ranch’s wholeness is its greatest asset—one worth protecting for future generations.

“It was important that both [my sister] and I grow up with an understanding that there was an importance in the wholeness of this ranch—having respect for your land and treating it as well as you can so that it’ll give back to you and be productive for years to come,” Hanna shares in the 2013 documentary “Hanna Ranch.” That understanding—and the tension of operating a ranch on the edge of rapid suburban and military-driven growth—would shape her life’s work.

Bridging Rural and Urban Worlds

Hanna holds a bachelor’s degree in urban planning and a master’s in ranch management, a pairing that mirrors her life at the intersection of two worlds.

“I was really interested in the rural–urban interface,” she explains. “Because I was raised on the front range, a lot of the pressures facing our ranch were related to urban and suburban expansion.”

Her early career stretched far beyond Colorado’s central grasslands. She began in private philanthropy, supporting rural community development in Colorado, then moved to the Pacific Northwest for an AmeriCorps role integrating public, private and philanthropic funding for rural and Indigenous communities across the Columbia River Gorge and eastern Oregon.

“I loved watching community-driven impact on the ground,” Hanna says. “Allowing communities to have a voice in their priorities was a big deal for me.”

Photo credit @Maggie Hanna

A Decade in Private Working Lands Conservation

Back in Colorado, Hanna spent a decade with the Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust—the nation’s first land trust founded by a producer organization. In the 1990s, long before collaborative conservation became commonplace, Colorado cattlemen recognized they shared long-term goals with conservation groups, even if they spoke different languages.

The resulting model of producer-driven conservation has since spread across 12 western states.

Hanna worked on perpetual conservation easements that safeguard working lands and keep ranches whole. What resonated most for her wasn’t just the land protection—it was what that stability made possible.

“Conservation easements are such a cool way to look at rural investment,” she says. “On one hand, you’re investing financially in a parcel. But you’re also investing in a community—helping people stay rooted for the long term. They join the school board, the fire department and raise their families there. That's the real economic impact in allowing people to commit to a place.”

Leaving Cattlemen’s, she recalls, “my heart was full.” But she also felt something bigger stirring.

“This is going to be a big moment for grasslands.”

Building the Central Grasslands Roadmap

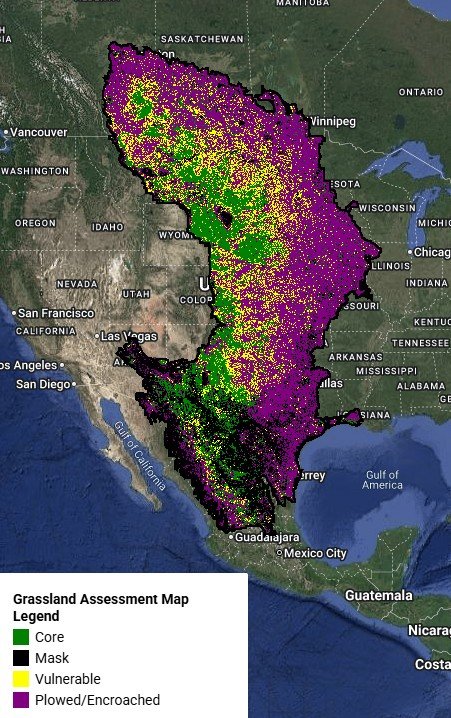

In February 2024, Hanna stepped into her role as director of the Central Grasslands Roadmap, an international initiative working across the 700-million-acre grassland biome spanning the central U.S., southern Canada and northern Mexico.

The Roadmap emerged from an insight within the migratory bird conservation community: saving one species at a time wasn’t enough. What grasslands needed was a holistic, collaborative, transboundary approach—one that prioritized intact landscapes, functioning ecosystems, sustainable livelihoods and thriving rural communities. The initiative’s chief catalyst was Tammy VerCauteren, Executive Director of Bird Conservancy of the Rockies.

“No bite is too big for Tammy,” Hanna says. “She said, ‘We’re going to do this across three countries, many Indigenous nations, 11 states, hundreds of counties and in multiple languages.’”

What has emerged since 2020 is a vast, diverse and uniquely collaborative conservation community—one Hanna describes as building “a longer table” for this ambitious conservation effort that includes more than 250 organizations and 700 leaders.

Here, modern-day Western science sits alongside Traditional Ecological Knowledge, a system of knowledge acquired by Indigenous peoples through direct interaction with the environment since time immemorial. Researchers collaborate with ranchers. Partners share data, capacity and strategies reach across borders.

“We need each other more than ever,” Hanna says. “Fear of scarcity pulls people away from collaboration, but collaboration is exactly what this ecosystem requires.”

The Most Imperiled Ecosystem on Earth

The urgency is real. Central grasslands are the most imperiled ecosystem on the planet—not because they are fragile, but because they are so easy to convert. So much so, the United Nations has named 2026 the Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists.

Grassland birds, whose migratory journeys span the entire biome, are the proof. Their populations have plummeted, and they serve as a warning sign: fragment the grasslands, and the whole system collapses.

“The landscape scale of this endeavor is big because it has to be,” Hanna notes, “If we destroy the middle of their migration corridor, nothing functions—not for birds, not for wildlife, not for us.”

Grassland birds use the entirety of this biome. They spend the winters in Chihuahua, Mexico, then migrate north in the spring and spend the summers in the northern Great Plains in northern Montana, North Dakota and southern Canada. And then they come back.

And if there’s a silver lining, it’s data. Because bird enthusiasts have logged sightings for decades, and the Central Grasslands Biome boasts one of the most robust citizen-science datasets in the world—crucial for decision-making.

“It’s amazing,” Hanna says. “Every birder who reports what they see is delivering very real conservation data. That means we all have the power to contribute.”

She continues, “I think we exist in a society that is desperate to make decisions on data. And that data doesn't necessarily exist for every species, and it doesn't exist for every community—but it does for birds in this biome.”

A Constellation Instead of a Hierarchy

The Roadmap is notable not just for its geography but its governance. Hanna describes the structure as “constellation governance”—no hierarchy, no single decision-maker, all consensus and co-learning.

She shares that their Indigenous partners have noted its similarity to tribal council models, and that mirroring is intentional and impactful. Hanna says, “It creates space for shared authority and shared responsibility.”.

Carbon Tour of Kit Carson Ranch, photo credit @Maggie Hanna

The initiative has an Indigenous Kinship Circle, a Mexico coordinator, and working groups on everything from international policy to bird-biome mapping to social-ecological research. Its priorities, set collectively in 2020 and 2022, will be revisited again in 2026.

“This biome is a relationship business,” Hanna emphasizes. “The bulk of the land is privately managed. Conservation only works when people trust one another.”

“Fast conservation,” she adds, just doesn’t hold in this case, something she knows personally as a rancher in the heart of the Central Grasslands. And one thing Hanna knows for sure is that durable conservation requires patience, creativity, and community.

The Underdog Worth Fighting For

Hanna has always loved an underdog. Grasslands, she says, are the ultimate example: undervalued, overlooked and yet doing some of the most important ecological work on the planet—water filtration, carbon sequestration, climate mitigation, wildlife habitat and sustainable livelihoods.

“If we don’t act now,” she warns. “We lose what’s left of the intact Central Grasslands.”

Yet she remains hopeful. States across the U.S. have appointed grassland coordinators. Cross-border collaboration is strengthening. The Roadmap will host an international summit in Chihuahua City, Mexico, in 2026—the initiative’s second in-person, tri-national gathering.

Photo credit @Maggie Hanna

And it’s no surprise that when asked about that hope, Hanna thinks back to growing up. She said she often thinks about the gap between what kids learn and where they live, “I grew up in the middle of the country, and we all knew about saving dolphins and sea turtles and sharks. But no one was talking about grasslands—even though we were living and working in them.”

Now, she’s determined to change that.

“Grasslands need loud voices,” she says. “And I think this is their moment.”

We’re in a defining moment—a moment where we can choose to be overwhelmed, disconnected and discouraged, or where we can choose to be positive, embrace change and lift up the work of others seeking a better future together. We’re proud to support the work of the people and organizations out changing this world for the better—for all of us. Some may be small, some large. All are mighty. Each month, we highlight one of our Mighty Partners and we encourage you to get to know them, support them, and share their work with your friends, families and colleagues. Let’s get to work.